“Let people say we’re in love,” the

chorus sings exultantly at the end of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival's production of Oklahoma! As the ensemble disperses this love all the way

to the back row of the audience, a rainbow-colored moon descends from the

ceiling. Laurey the farm girl, after struggling to express her sexuality, marries her beloved wife, the charming cowhand Curly, in a ceremony marked by

celebration and acceptance from their community. Not even a drunk, homophobic

Jud, who falls on his own knife after Curly fails to stop him from committing

suicide, can dampen the festivities.

|

| The OSF ensemble joyously sings "Oklahoma!" |

Then the cast bows and belts out a

rousing reprise of the title number. When they reach the lyric, “We know we belong to the

land, and the land we belong to is grand,” they declare that LGBTQ people have

a claim on America and its promise of equality. Their final, jubilant “Yeow!”

invites the audience to cheer for the country’s increasing acceptance and

inclusion.

Though the audience still claps,

probably out of habit, perhaps a more appropriate response to the venomous,

angry “Yeow!” that concludes the current Broadway revival of Oklahoma! is

stunned silence. Laurey the farm girl, after struggling to express her

sexuality, has married the trigger-happy cowman Curly; maybe because she loves

him, maybe because he offers her greater protection on the chaotic frontier, or

maybe because she has no other option; in a ceremony marked by violence and

bloodshed. A calm, well-dressed Jud arrives at the scene, kisses Laurey, and

gives Curly a gun as a wedding present. Jud seems to take a step toward Curly

and Curly shoots, killing Jud, his blood splattering over Curly and Laurey’s

white wedding outfits.

|

| Curly and Laurey's wedding outfits will soon become blood-stained |

The “Oklahoma” reprise that follows

the hastily assembled murder trial, during which Laurey’s Aunt Eller sinisterly

threatens the federal marshal unless he lets Curly off the hook, is sung with

tortured ambiguity, an intensification of Laurey’s internal struggles

throughout the play. When they sing, “We know we belong to the land, and the

land we belong to is grand” it sounds like an unsettling question rather than a

confident expression of belonging. Their scowling faces and aggressive body

language suggest that America can’t honestly promise sunny optimism, but only confusion

and brokenness, from the barrel of a gun.

|

| OSF's Oklahoma! ensemble featured gender non-conforming performers |

The contrasting “Yeows!” demonstrate

that non-traditional productions of this old warhorse of a musical can draw out

drastically different meanings from it. Director Bill Rauch’s Oregon production

is non-traditional because of its casting: Curly is played by a woman as a

woman, Ado Annie becomes Ado Andy and is played by a man, Aunt Eller is trans,

Ali Hakim is bisexual, and the ensemble features gender non-conforming performers.

Jud remains a man. But beyond the casting, some significant changes to the

dream ballet, and mostly trivial revisions of the script around things like

gender pronouns and “cowman” becoming “cowhand,” the production is a standard

interpretation of the material with conventional staging, familiar

orchestrations, and period costumes.

Daniel Fish’s Broadway production

maintains the traditional gendered casting, but otherwise makes much more

significant deviations from how Oklhaoma! is usually presented. It

features a stripped down cast of just 12, re-orchestrates the score to have a bluegrass

sound, uses anachronistic costumes and props—the hampers prepared by the women are

Coleman coolers rather than frilly baskets, keeps the lights on the audience

for most of the show, has guns hanging from the wall as the most prominent part

of the scenery, and reworks the dream ballet into a virtuosic, one-woman,

modern dance piece.

|

| Ali Stroker as Ado Annie |

Both productions should be credited

for their inclusive casting decisions. In addition to LGBTQ representation in

the Oregon production, black actors play Curly and Will, an actor of Middle

Eastern descent plays Ali Hakim, and the ensemble features many performers of

color. On Broadway, Laurey and her dream counterpart are played by black performers,

and two male actors of color have small speaking roles. Ado Annie is played by

Ali Stroker, the first wheelchair user to perform on Broadway. Her twangy “I

Cain’t Say No” brings the house down. The empowered sexuality she brings to the

role pushes against negative stereotypes of people with disabilities as sexless

or undesirable. While it was fun to watch Ado Andy sing that song too, popular

culture does not lack portrayals of oversexed gay men.

|

| Royer Bockus and Tatiana Wechsler as Laurey and Curly |

Another characteristic shared by

both productions is the close attention they pay to Laurey. This makes sense:

the central conflict of the show is Laurey’s choice between Curly and Jud. In

the Oregon production, this choice could have been easy for Laurey. She is gay.

Curly is female. Jud is male. But Laurey is still coming to terms with her

sexuality. A question left by the script of Oklahoma! is why Laurey

lives with her Aunt Eller and not with her parents. This production suggests an

answer: she may have been running away from a home that rejected her for being

gay and found a safe place to live with her trans aunt in a more affirming

community. So Laurey’s ambivalence toward Curly has less to do with her

attraction to Jud, and more with how the trauma of the closet continues to

weigh on her psychology. In this production, “People Will Say We’re in Love”

becomes much more than a coy love song. Laurey knows that there could be

consequences for her if people knew she loved a woman.

|

A happy moment in the "Dream Ballet"

before Jud turns it into a nightmare |

This sub-text becomes text in the

reimagined dream ballet. Dream-Jud is dangerous not because he represents

unrestrained sexuality, but because he signifies homophobia and transphobia. In

this version, the can-can girl sequence of Agnes De Mille’s original

choreography starts when Jud menacingly forces Laurey’s gender non-conforming

friends to change clothes. Laurey is truly afraid of how Jud might hurt her or

Curly, which is why she ultimately decides to go to the box social with him.

When Laurey fires Jud in act two, it’s portrayed as a moment of liberated

empowerment. She overcomes internalized and external homophobia to finally let

the world know that she and Curly are in love.

When Jud returns to crash their

wedding, he sneers at Curly, saying he has a present for the “groom,” which is

the only time the production opts not to change the gendered terms of the

script. Jud starts to attack Curly but then appears to turn the knife onto

himself. The audience sees Curly grab the knife to stop Jud from killing

himself, but in the resulting scuffle, Jud falls on it and dies. The other characters

do not see the same details as the audience, but Curly is nonetheless acquitted

in a humorous trial. Aunt Eller still threatens the marshal, but it’s funny

rather than sinister. Though the threat posed by Jud is subdued by his death,

the final scene reads as a reminder that even with increased acceptance, the

threat of violence against LGBTQ people remains.

But this production insists on a

happy ending, something too few queer characters get. The closing image of the

rainbow moon over a now-wed Laurey and Curly represents the comfort and love so

many LGBTQ people find with their chosen families after experiencing what can

be painful rejection. Laurey’s story of ultimate belonging is exuberantly

reflected in the singing of “Oklahoma” and punctuated with its final “Yeow!”.

This production presents an aspirational vision for an ever more inclusive America.

|

| Gabrielle Hamilton dances the re-imagined "Dream Ballet" |

The depiction of Laurey on Broadway

offers a much darker, though possibly a more realistic, depiction of America as

a bewildering and violent country. This Laurey seems to know that her fate on

the plains is tied up with the whims of the belligerent men who surround her.

She feels intense sexual desire for them, but she knows sex could be dangerous.

Romance is distant. The dream ballet dancer, representing Laurey’s psyche and

wearing a sparkly shirt that says “Dream Baby Dream”, is voracious, galloping

around the stage like a horse, making eyes at the audience, flirting with male

and female figures on stage, and helping Laurey pleasure herself, all as an

electric guitar plays a distorted and almost hostile rendition of the score. It

looks and sounds completely different from De Mille’s original choreography,

but just as in the original, it translates Laurey’s id into thrilling movement.

|

| The audience is invited onstage for chili during intermission |

The lighting also calls attention to

Laurey’s arc, uncovers new insight into Curly and Jud, and narrows the gap

between audience and performers. The lights are up on the audience for almost

the entire show. This choice makes the audience part of the community depicted

on stage, which otherwise would feel insubstantial due to the small cast. Audience

members literally take the stage during intermission to eat chili simmering in

crockpots and the cornbread that Aunt Eller and Laurey prepared at the

beginning of the act. The lights also implicate the audience in the happenings

of the show. We become auction participants, wedding guests, and witnesses to

Jud’s killing. But because the show is performed in the round, audience members

may draw different conclusions about the actions on stage based on their seat

locations, mirroring how cell-phone video and dash-cam footage of contemporary

shooting deaths simultaneously turn us all into witnesses while offering

competing perspectives.

|

| Damon Daunno and Rebecca Naomi Jones as Curly and Laurey |

The lighting occasionally changes,

signifying tension and drama. When Curly sings the third verse of “Surry with

the Fringe on Top” about the sun swimmin’ on the rim of a hill, an eerie green

light floods the stage, not the purplish-red sunset lighting that we might

expect, and which was used for this moment in the Oregon production. At the end

of “Many a New Day,” which Laurey sings spitefully rather than playfully (in

Oregon, Laurey tap-danced), when she croons about many a red sun setting, the

same green light returns. Hammerstein’s poetic, romantic lyrics become murkier

in green, evoking something disquieting about Curly and Laurey’s feelings for

one another, like an Oklahoma sky before a tornado strikes.

|

| Red club lighting during "People Will Say We're in Love" |

Red light does fill the stage during

Curly’s verse of “People Will Say we’re in Love,” but it’s the artificial light

of a rockabilly club, not the natural light of the outdoors. Curly sings it as

a knowing performance—Laurey mentions that Curly is playing guitar, which he

had done earlier during “O, What a Beautiful Morning” and “Surrey with the

Fringe on Top” without any of the other characters commenting. In other

productions of Oklahoma!, including the one in Oregon, Curly’s

observation: “your hand feels so grand in mine,” is a moment of vulnerability,

an honest expression of a private feeling, not something visible that people

could then gossip about all day behind their doors. Here though, it’s sung with

ironic detachment, as Laurey sarcastically dances in front of him. The song

still ends on a note of sexual tension between the two, but the romance is far

less secure.

|

| An erotic moment at the end of "Poor Jud is Daid" |

The most striking lighting choice

occurs in the very next scene, when Curly confronts Jud in his smokehouse. The

lights suddenly go out, leaving the entire theater, including the actors on

stage, in total darkness. In this production, the smokehouse isn’t creepy

because of its dirt and pornography, but rather because of the anxious

one-upmanship between Curly and Jud, expressed only through their voices. When

Curly taunts Jud with “Poor Jud is Daid,” a camera streams an extreme close-up

of Jud’s face, which is projected onto the back wall of the stage. Patrick

Vaill’s performance as Jud during this scene is stunning, conveying at once

pride, insult, anger, and sadness as Curly describes what his funeral would be like.

A single tear falls from his eye. The song ends with Curly’s and Jud’s lips

just an inch apart, a haunting, sexually charged image.

Curly’s drive for sex and violence

is just as pronounced as Jud’s, but his popularity and charm make others in the

community—except for perhaps Laurey—more willing to overlook those darker

features of his character. Jud is not granted the same leeway. His “Lonely

Room” soliloquy that follows reveals his deep desire for belonging in this

community that sees him as unwanted and scary. Because of the sexually charged

nature of these plains, Jud seems to believe he can find that belonging only by

winning over Laurey.

|

The cast's colorful costumes during "The Farmer and the

Cowman Should be Friends" |

The stage goes black once more in

the second act. Jud and Laurey are alone after Curly embarrasses him by winning

Laurey’s hamper at the auction, during which Jud bid two years’ worth of

savings for it. Unlike in other productions, Jud participates in the “Farmer

and the Cowman” sequence before the auction, even smiling along with everyone

else. But while most others onstage wear a color that connects them to another

character—Laurey and Curly in blue, Will and Ado Annie in yellow—Jud’s blue and

brown checkered shirt is matched only by Ali Hakim. The costuming communicates

to the audience that these characters are outsiders; the way they are treated

during the auction surfaces their outsider feelings all the more so.

So when Jud and Laurey are alone, he

has one further shot at gaining the belonging he so craves. The lights go pitch

black as Jud tenderly shares memories of when Laurey took care of him when he

was sick. The audience hears Jud go in for a kiss and it sounds like Laurey

kisses him back. The darkness leaves it ambiguous as to whether she gave her

kiss with consent. We hear Jud start to unbuckle his belt. The lights go on

again and Laurey pulls away, firing Jud and sending him away from the

community.

They stay on when Jud returns to

crash Curly and Laurey’s wedding. He says he has a present for the groom but

first wants to kiss the bride. He actually kisses Laurey with no apparent

resistance from her. Is she scared into submission? Does she still harbor some

desire for Jud, even after marrying Curly? The whole sequence is disconcerting,

ending with Curly shooting Jud, maybe in self-defense, and blood staining Curly

and Laurey’s wedding clothes. It all takes place in full, bright light, but

it’s uncertain what actually happens.

|

Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones, and Patrick Vaill as

Curly, Laurey, and Jud |

In total, these lighting choices unearth

different potential motivations for Jud, Curly, and Laurey while keeping the

text intact. The production does not absolve Jud for believing his ticket to

acceptance lies exclusively in how one woman feels about him, but the lighting

helps the audience understand what exclusion feels like viscerally. It strips

Curly of his status as the ur-Romantic Hero of the American Musical canon, by

revealing the dark and unsafe sides of his personality.

The lighting also suggests that whatever

romance Laurey might feel for Curly and Jud is not obvious to her or to the

audience, right up until the very end. Laurey and Curly’s marriage remains

symbolic of Oklahoma’s ‘marriage’ into the United States, but instead of being

hopeful, the union is more unsure, self-conscious, and dangerous. The lighting

helps the audience feel both Laurey’s personal ambivalence about her life

circumstances and relationships as well as ambivalence toward what it means to

be American. It all becomes nearly unbearable for Laurey and the rest of the

ensemble during the final reprise of “Oklahoma,” culminating in their scathing “Yeow!”

The conflicting interpretations of

the same material in these productions suggest that classic musical theater can

be as robust as Shakespeare, open to all kinds of experiments. These particular

interpretative choices; one which makes Oklahoma! an aspirational show about

American belonging (à la Hamilton) and one that does not flinch from the

American reality of violence, sex, and power (à la the oeuvre of Arthur Miller);

have contemporary political resonance. Indeed, these productions can be seen as

proxies for the opposing strategies seen so far in the 2020 presidential

election.

A candidate like Pete Buttigieg, who

emphasizes hope and belonging from the stump, earnestly believes in American

values and sees them as a positive force in the world, and has a more-or-less traditional

marriage save for the gender of his spouse, aligns almost perfectly with the conventionally

staged world of the OSF production and its message of inclusion. Beto O’Rourke

says his meetings with regular folks on the campaign trail make him feel

optimistic about the future of the country. OSF’s Oklahoma! had a

similar impact on audience members. Joe Biden, who calls Trump an aberrant figure

in American political life, could reasonably say the same thing about this Jud.

A candidate like Pete Buttigieg, who

emphasizes hope and belonging from the stump, earnestly believes in American

values and sees them as a positive force in the world, and has a more-or-less traditional

marriage save for the gender of his spouse, aligns almost perfectly with the conventionally

staged world of the OSF production and its message of inclusion. Beto O’Rourke

says his meetings with regular folks on the campaign trail make him feel

optimistic about the future of the country. OSF’s Oklahoma! had a

similar impact on audience members. Joe Biden, who calls Trump an aberrant figure

in American political life, could reasonably say the same thing about this Jud.

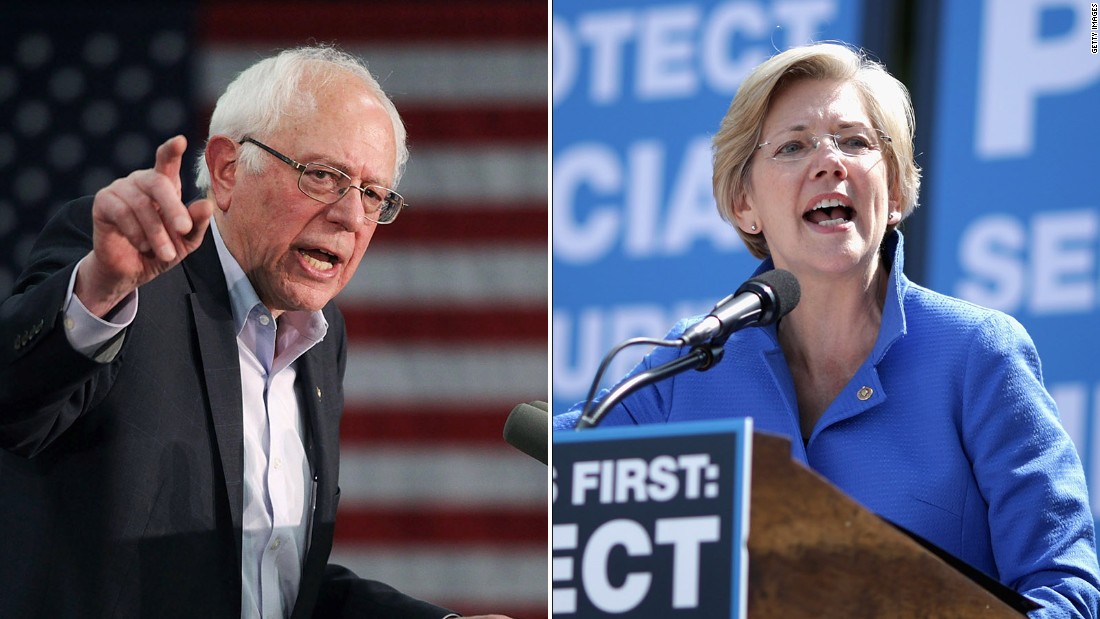

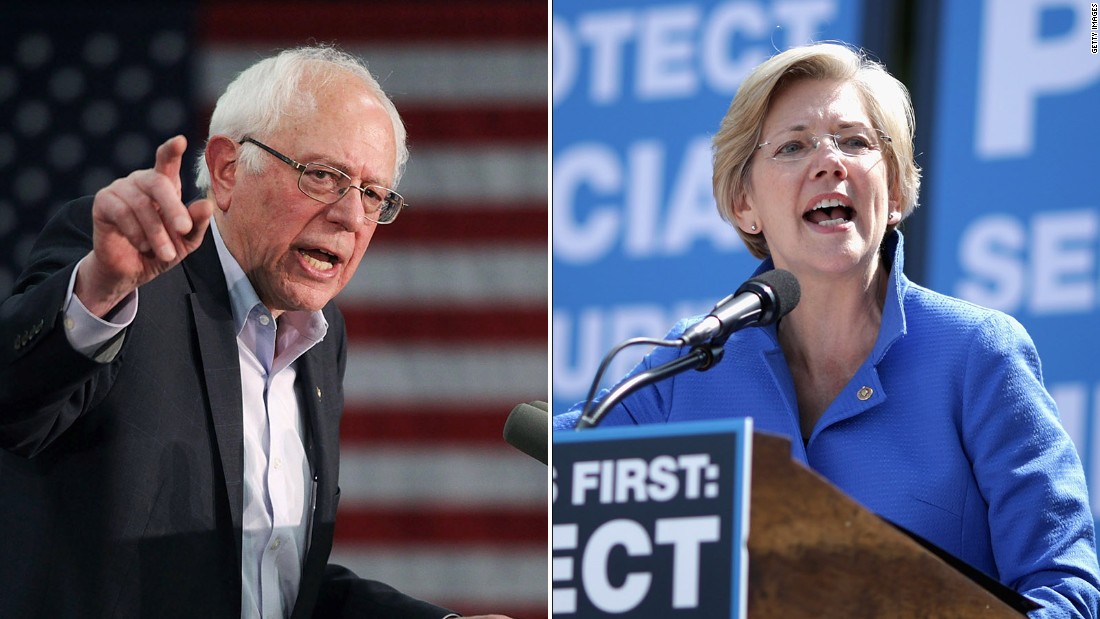

Other candidates evoke the themes of the Broadway revival. Elizabeth Warren, who grew up in Oklahoma, foregrounds

how Washington corruption ensures that only the well-connected have their interests

protected. Such corruption occurs right in the open on Broadway as Aunt Eller

uses her influence to get Curly cleared of murder. Bernie Sanders speaks out

against the military industrial complex and actually uses the term, intimating

that America is structured in a fundamentally violent way, just as Broadway’s Oklahoma!

does.

Other candidates evoke the themes of the Broadway revival. Elizabeth Warren, who grew up in Oklahoma, foregrounds

how Washington corruption ensures that only the well-connected have their interests

protected. Such corruption occurs right in the open on Broadway as Aunt Eller

uses her influence to get Curly cleared of murder. Bernie Sanders speaks out

against the military industrial complex and actually uses the term, intimating

that America is structured in a fundamentally violent way, just as Broadway’s Oklahoma!

does.

To be sure, these candidates are not

as fatalistic about America as the production is—they are still running for president

after all, which implies a belief that under their leadership, circumstances could

improve. In a disturbing way, then, Trump could be the 2020 presidential

candidate most aligned with the world depicted in this Oklahoma! His evocation

of “American carnage” along with the hostile attitude he exhibits toward

outsiders make it plausible that Curly and Aunt Eller would wear MAGA hats to

the next box social.

To be sure, these candidates are not

as fatalistic about America as the production is—they are still running for president

after all, which implies a belief that under their leadership, circumstances could

improve. In a disturbing way, then, Trump could be the 2020 presidential

candidate most aligned with the world depicted in this Oklahoma! His evocation

of “American carnage” along with the hostile attitude he exhibits toward

outsiders make it plausible that Curly and Aunt Eller would wear MAGA hats to

the next box social.

Laurey, as is her way, would

probably be less certain of which candidate to support. Likewise, had she been

in the audience at OSF and on Broadway, she might struggle to say which she enjoyed

more. But while politics would force Laurey to choose just one person, as the

plot of the musical does, the richness and flexibility of theater would allow

her to dream, baby, dream as she made up her mind about her favorite Oklahoma!,

or not.

|

Thursday Williams and Heidi Schreck debate at the end of

What the Constitution Means to Me |

Broadway audiences this season are

lucky that a different version of this deliberation about the meaning of

America occurs just a few blocks away from Oklahoma! At the end of What

the Constitution Means to Me, Heidi Schreck and a high school-aged girl

debate whether or not to abolish the constitution. Is the American system

fundamentally flawed, incapable of recognizing the humanity of outsiders? Or is

it possible that the constitution’s core message of “We the People” can be

expanded? The answer could be different in every performance.

So too with our reactions to these Oklahomas!

and their “Yeows!” On days following mass shootings, in the aftermath of

white supremacist violence, when confronting pervasive sexual assualt, and

while fighting all forms of injustice, we should be honest about the

shortcomings of the American dream and make sure those in power hear about it

with our raw and persistent “Yeow!” But that wave of anger can be joined by

other emotions. All together, these feelings can help us find the courage to be

optimistic enough to work toward an America in which more people feel a sense

of belonging. Doing that work is not easy, but sprinkling it with an

occasional, joyful “Yeow!” might help.